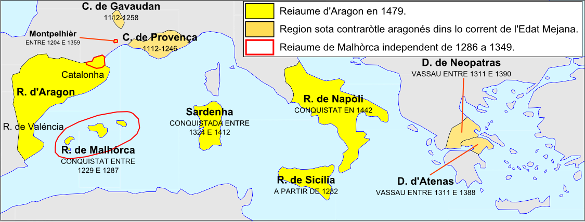

Jessica L. Minieri is a PhD Candidate in the Department of History at Binghamton University (SUNY). Her dissertation project, ‘Stolen Bodies and Hollow Crowns: Abduction and Imprisonment in the Lands of the Crown of Aragon, 1200-1415’, explores the broader histories of captivity, forced marriage, and imprisonment in Sicily and Mallorca. Jessica is also a member of the Medieval and Early Modern Orients (MEMOs) Project and an editor of H-Sicily. You can learn more about her work at https://www.jessicalminieri.com/.

In the months following the election of Robert of Geneva as Pope Clement VII in Avignon in opposition to Urban VI in Rome, the young queen of Sicily, Maria, was kidnapped and dragged away from Castello Ursino in Catania. Guglielmo Ramon Moncada, an ally of Maria’s grandfather, Pere IV ‘El Cerimoniós,’ entered Castello Ursino to capture Maria and take her away from one of her four regents, Artale Alagona, and bring her into Aragonese custody. King Pere IV wished to bind Maria into marriage with one of the members of his direct line in order to end Sicily’s semi-autonomous status within the Crown of Aragon and take the throne for himself. The sixteen-year-old queen Maria was the last surviving member of her dynasty and the token by which Aragon, through her sexual reproductive potential, could make a direct claim to the monarchy in Sicily.

As Moncada dragged Maria away from Catania and brought her to the city of Licata, Maria’s regents – Alagona, Manfredi Chiaramonte, Francesco Ventimiglia, and Guglielmo Peralta – worked to release her from Moncada’s custody and bring her back into their possession. Their efforts were not noble, however, as her regents aimed to imprison her themselves and marry her to Gian Galeazzo Visconti in Milan. Their goal was to prevent the Aragonese from controlling her marriage and to limit further Aragonese encroachment in Sicilian politics.

After Maria’s abduction, her four regents remained in Sicily with the intention of ruling the island amongst themselves and seeking an alliance with the Roman Pope, Urban VI. During the period of ten years when Maria was living in Aragonese custody, the Crown of Aragon maintained a neutral stance in the Papal Schism to keep its polities outside of the Papal entanglement. While the Crown of Aragon did not take an official stance in the Schism during the life of Pere IV (d. 1387), his heir, Joan ‘the Hunter’, did support the papacy in Avignon and pledged to support Clement VII once king. This stance allowed Maria’s Sicilian regents to take advantage of her position as a hostage by appealing to Rome for an alliance and requesting intervention in the conflict.

The alliance between Urban VI and Sicily aimed to accomplished two important goals for both the Sicilian nobles and the broader papal project: 1) an alliance between the Sicilian nobility and the Roman Pope would provide the support that the Roman church needed to stake its claim to the island; 2) in gaining the trust of the nobility, Urban VI could persuade them not to allow Maria to return to the island with an Aragonese husband by mounting an armed resistance. This alliance proved fruitful by 1383 when in a letter drafted to the four regents, Urban VI issued a proclamation that Maria could not return to the island with an Aragonese husband and expect to reclaim her throne.[1] Any hope that Maria had to reclaim her throne according to the Roman Curia, only existed outside any connection to the ‘schismatic’ Aragonese or any other foreign power.

Unfortunately for Maria, the choice of marriage was not hers alone to make. In 1383, while she remained under the custody of Roger of Moncada – a relative of her captor and an ally of King Pere IV – at the Castello de Caller in Cagliari, plans were drafted in Barcelona to petition Clement VII in Avignon for a papal dispensation to marry her into the House of Barcelona.[2] Pere IV wished to marry Maria to his grandson, Marti, as his original candidate for her hand, his son Joan, married Violante of Bar against his father’s wishes. As grandchildren of Pere IV, they needed papal permission to marry, or their union would be considered illegitimate. Despite the approval of their union from Avignon, Maria remained a prisoner of the Aragonese until 1390. Between 1379 and 1390, she was held in a series of castles in Aragonese strongholds across the Mediterranean. Once plans were finalized for her to marry Marti in 1390, she was then released from her confinement and allowed to join her husband in the Aragonese court.

Once the two were wed, plans were made to restore Maria and Marti to the Sicilian throne as co-rulers with the aid of Marti’s father, Martin of Aragon. Maria’s return to Sicily was the first time that she had been back to the island since 1382 when Pere moved her to Cagliari. Her homecoming was not one of joy, however, since her return alongside Aragonese forces led to years of bloodshed. All her vicars apart from Manfredi Chiaramonte, relinquished their ties to the Roman Curia and to Aragonese resistance after months of violence and invasion plagued the island. Chiaramonte’s resistance, however, led to the death of his son, the loss of his titles – including the County of Malta – and the loss of the Palazzo Chiaramonte-Steri in the heart of Palermo.

This period of violence concluded when Maria and Marti were crowned in Palermo Cathedral in May 1392. Between their coronation and Maria’s death in 1401, the two ruled the island, although the Sicilian nobility continued to struggle to accept the rule of King Marti. As the Schism wore on, Sicily’s ties to Rome dissolved as Maria’s regents were ousted and Marti pledged obedience to Pedro de Luna, an Aragonese nobleman and the new head of the church in Avignon.

Ultimately, Maria’s reign, imprisonment, and role in Sicilian politics was one characterized by violence, schism, and control. During her time as an Aragonese prisoner, the fates of her reign and throne were determined by the men controlling her body in Aragon, the men controlling her kingdom in Sicily, and the papal thrones in Rome and Avignon. Maria – both as a queen and a determinant of the Sicily’s future – marked a turning point in Sicily’s relationship with Iberia and its relationship with the Latin Church. In the years following her 1401 death, Sicily would, once again, be plagued by brutality and intrigue as her successor and the second wife to Marti, Blanca of Navarre, similarly ran from the Palazzo Chiaramonte-Steri to escape her own imprisonment.

[1] Enrico Stinco, ed., La politica ecclesiastica di Martino I di Sicilia (1392-1409) (Palermo: Boccone del povero, 1920), 4-5 (Doc II).

[2] Archivio di Stato di Palermo, Protonotaro del Regno, vol. 6, f. 59r-60r.